The Myth of the End of Ideology

Preface: This article examines the persistent role of ideology in human society from a Marxist perspective, challenging claims that the “age of ideologies” has ended. It situates ideology not as mere illusion or falsehood, but as a reflection of class relations and social reality, highlighting the unique nature of Marxist theory as both critical and consciously rooted in the interests of the working class.

“The theoretical fog these learned gentlemen raise serves only to conceal the fact that they are leading the movement into a swamp.”

— Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, theorists and spokespeople of the global bourgeoisie have persistently proclaimed the “end of the age of ideologies,” and they continue to insist on this claim. Even some individuals and currents that identify themselves as “left” have come to believe that the era of ideologies has indeed come to an end, repeatedly admonishing other leftists to accept this fact and to abandon an ideological approach to social and political questions.

But has the age of ideologies truly come to an end? Are we now living in a non-ideological world? Is ideology merely a product of our minds—something imposed upon the world by our own subjective interpretations—or are ideologies themselves products of objective realities within human society?

To answer these questions, we must first clarify what ideology is and where it originates. Without resolving this issue, any discussion of the “end” or “persistence” of ideology inevitably becomes either entirely abstract or reduced to moralistic and subjective judgments.

Contrary to widespread but mistaken interpretations attributed to Marxism, Marxism does not define ideology merely as a collection of false ideas, nor does it reduce it to a simple instrument of deception.{1} Rather, it understands ideology first and foremost as a specific form of social consciousness rooted in material relations and the class structure of society. In a society founded upon class divisions, individuals do not experience their social world directly and without mediation; this experience is always filtered through their class position, social role, and place within the relations of production. Ideology emerges precisely in this sphere—as an inverted, partial, or one-sided reflection of social reality that nevertheless appears entirely real, self-evident, and natural to those who bear it. This is what Marx refers to as “false consciousness.”

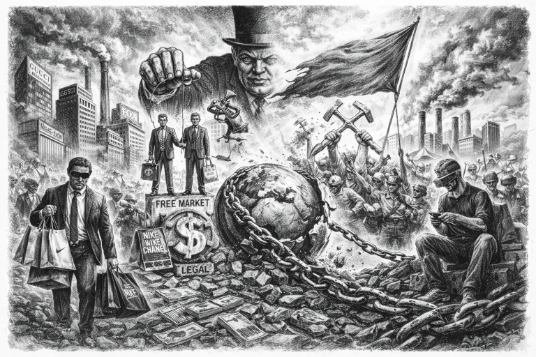

Nevertheless, in any critique of bourgeois ideology one cannot overlook its central point of departure: the individual and individualism. By placing the “individual” at the center of the human world, bourgeois ideology effectively pushes society, class relations, and material structures—indeed, the social being of human beings as such—to the margins, and seeks the roots of inequality, poverty, and oppression not in the social system itself, but in individual traits, choices, or failures. This individualism, in its inner connection with consumerism and commodity fetishism—both products of the capitalist mode of production—brings into being a world in which relations between people appear as relations between things, and commodities come to bear meaning, identity, and power. In such a world, the human being is defined not as a social and historical subject, but as a consumer, seemingly destined to seek liberation, freedom, and the meaning of life in the accumulation of wealth, in the realm of the market, and in the endless consumption of commodities. Thus, within the inverted image of this inverted world, everything appears ostensibly “self-evident” and “natural.”

For this reason, it must be emphasized that Marxism has never reduced ideology to “lies,” nor does it do so now. Ideology can contain real elements, concrete and practical experiences of everyday life, and even forms of protest against the existing order. For example, when a worker complains about “unfair wages” or the “greed of the employer,” this complaint is grounded in a real experience. Yet if this dissatisfaction is articulated within the framework of the belief that the problem lies merely in the unjust behavior of this or that capitalist—rather than in the social relation of capital itself—this very real protest easily turns into a form of ideology (false consciousness) that leaves the existing relations intact. In other words, reality is perceived, but its roots remain concealed.

The same logic operates on the side of capital. When bourgeois ideology speaks of “legal equality” and “freedom of contract,” it is dealing with concepts that are entirely real. Worker and capitalist are indeed equal before the law, and they do in fact enter into contracts freely. Yet this equality and freedom, abstracted from the materially unequal conditions of the two parties—that is, without regard to the reality that they occupy profoundly unequal socio-economic positions—are presented in an inverted form. This presentation does not negate exploitation; on the contrary, it legitimizes it. Here too, ideology incorporates elements of reality and does not simply lie; rather, it substitutes a partial and one-sided reality for the totality of social relations.

Even many ostensibly critical discourses can function in this way. When the crises of capitalism are attributed to “corruption,” “inefficient management,” or “individual greed,” we are again confronted with real elements. Corruption, inefficiency, and greed undeniably exist. Yet by reducing crisis to individual failures, attention is diverted away from the logic of capital accumulation itself and its internal contradictions. Critique thus degenerates into superficial reforms (for example, raising or lowering taxes, or simply replacing managers), instead of leading to a negation of the existing relations.

In all these examples, ideology appears not as a pure fabrication of reality, but as a particular mode of representation—a representation that articulates real elements from a perspective and within a framework compatible with the totality of existing social relations and that ultimately contributes, indirectly, to their reproduction. This is precisely why ideology can be persuasive, durable, and even seemingly critical, without ever transcending the boundaries of the prevailing order.

It is within this framework that we must understand why Marxism itself is also an ideology—a point that is sometimes denied consciously and sometimes out of misunderstanding. Marxism undoubtedly offers a scientific critique of political economy, a materialist analysis of history, and a specific method for understanding society. Yet these qualities do not exempt it from being ideological. Marxism is the ideology of the proletariat: the theoretical expression of the historical interests of a class that seeks its emancipation not through reforming the existing order, but through the abolition of all class relations. The difference between Marxism and the ideologies of the ruling classes, therefore, does not lie in Marxism being “non-ideological,” but rather in the fact that, first, Marxism presents reality not superficially or in fragmented form, but in its depth and totality; and second, unlike the ideologies of the exploitative classes, which present their own partial interests as the interests of all, Marxism consciously and openly foregrounds its connection to its class position and makes no attempt to conceal it. Marxism insists on class antagonism and openly proclaims the conflict between the interests of the working class and other exploited strata and those of the parasitic capitalist class. It was no accident that Marx and Engels declared plainly in The Communist Manifesto that “The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions.” This is one of the fundamental points of distinction between Marxism and other ideologies.

Another important point, which cannot be addressed here in detail but should at least be mentioned briefly, is the distinction between a ‘class in itself’ and a ‘class for itself’ in Marx’s analysis of ideology. The reality is that the bourgeoisie, as a class conscious of its own material and historical interests, consciously organizes its ideology and imposes it upon society as a whole in order to secure its class interests and the reproduction of the social relations aligned with them. This ideology is real insofar as it corresponds to the class interests of the bourgeoisie and, in that sense, cannot be regarded as false consciousness. However, when the same ideology is taken up by the working masses and the oppressed layers of society, it functions as false consciousness for them, insofar as it does not encompass their own interests. Therefore, if the working class is to realize its immediate and historical interests, it too must arrive at an awareness of its own real interests. Marxism, in this precise sense, is the theoretical articulation and expression of proletarian class consciousness, and the terrain through which the working class can transform itself from a class in itself into a class for itself.

Nevertheless, it should be added that class society itself is the social and historical expression of humanity’s alienation—from itself, from the product of its labor, from other people, and from nature. Any form of class consciousness, as long as it remains confined within the narrow bounds of these relations, remains in a sense a kind of false consciousness, because it does not perceive humanity and its interests in their full totality. The fundamental and decisive difference between Marxism, as the ideology of the working class, and the ideologies of exploiting classes lies precisely in the fact that its aim is not merely to shift or perpetuate class domination in another form, but the ultimate abolition of classes and class domination—that is, resolving human alienation and providing the possibility for a direct, unmediated understanding of oneself and the surrounding world. It is only at this historical juncture that ideologies finally wither away, and the only guiding light for humanity will be a science liberated from ideology and class politics{2}.

In his Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, in the famous section on religion, Marx lays bare the origin and essence of religion—as the earliest manifestation of ideology in the inverted and alienated world of class society:

“Man makes religion, religion does not make man. Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet found himself or has already lost himself again. But man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man—state and society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d’honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal ground of consolation and justification. It is the fantastic realization of the human essence, since the human essence has no true reality. The struggle against religion is therefore indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion.”

If ideology is the inverted expression of an inverted world, then the negation of ideology without the negation of that world itself is nothing but self-deception. But how can such a world be negated? Can it be overcome without concrete steps and without the necessary instruments for change? Can one evade the inevitable historical process and conquer reality through sheer will—that is, in an abstract manner? No. The entire history of humanity testifies that transformation and revolution are impossible without breaking the organized coercion of the ruling class and without resorting to the organized power and revolutionary force of the masses. The invaluable experience of the Paris Commune and its bitter defeat stands as proof: it demonstrated that the rule of the majority—even if backed by overwhelming consensus—cannot survive the naked and ruthless violence of counter-revolution without its own organized defensive apparatus and revolutionary power.

From this perspective, speaking of the “end of ideology” in a society that remains deeply class-divided and ensnared in relations of domination is nothing but misunderstanding or deception—even if those who make such claims are not consciously aware of it or do not intend to deceive. When it is said that ideology no longer exists, it is in fact the dominant ideology that presents itself as pure rationality, sheer realism, or a “non-ideological” discourse and thereby imposes itself upon the masses. Is liberalism not an ideology? Is neoliberalism not an ideology? Are the glorification of private property, the market, the capitalist order, and its so-called “free world” not expressions of ideology? At a time when the profoundly reactionary and inhuman capitalist system wrings the necks of billions across the globe and simultaneously legitimizes the hell it has created on earth through its own ideological principles, to speak of the end of ideology—and to preaching the left about abandoning ideology—is, if not outright deception, at the very least stupidity. Communists and other progressive forces must not lose sight of this fact, for the negation of ideology itself becomes an ideological weapon for disarming the working class and the oppressed masses.

In fact, removing ideology from the equation of class struggle paves the way for undermining the very notion of struggle. The negation of ideology leads in practice to the negation of class politics, and the negation of class politics to the negation of forms of organization and the exercise of power by the working and laboring masses. Once ideology is deemed superfluous or dangerous, the party, the state, and every centralized form of political power are called into question. As a result, the material and indispensable instruments for the transition from capitalism to socialism- the only path to rescue humanity from the quagmire of suffering, bloodshed, and oppression under capitalism- are removed from the equation, and the advance of struggle is rendered sterile.

Thus, the “end of ideology” is not a reality, but itself an ideological myth—one that seeks to deny the existence of ideology without abolishing the relations that generate it. The truth is that as long as human society remains a class society, ideology will persist and continue to exist. And if there is anything whose end can truly be proclaimed and justified, it is not ideology itself, but the illusion that ideology can be abolished without a material transformation of the world.

A. Behrang

February 6, 2026

Notes:

{1} This view is most clearly articulated in liberal–positivist critiques of Marxism, notably in Karl Popper’s treatment of Marxism as a closed, pseudo-scientific system.

{2} It is clear that with the end of the history of class society, history does not cease as conscious human action; instead, it is for the first time released from the grip of irreconcilable class antagonisms.