Philosophical Antagonism between Marxism and Religion

(With a look at The Organization of the Iranian People’s Mojahedin and its ideological developments in the first half of the 1970s)

The founders of the Organization of the Iranian People’s Mojahedin (OIPM), as a symbol of the revolutionary petite-bourgeoisie in the democratic and anti-imperialist movement of our country, acknowledged the scientific-philosophical superiority of Marxism and its indisputable role in revolutionary practice in the contemporary world. And with that acknowledgement, they tried to amalgamate and arrange petite-bourgeois revolutionism with proletariat themes. The result was an eclectic philosophical doctrine that was committed to Islam while also interested in some aspects of Marxism. This, however, was neither coincidental nor was it limited to Iranian society, but rather an historical and global tendency.

The petite-bourgeoisie— during the beginning of the rule of the big bourgeoisie in the metropoles in the 19th century, and also later on during the expansion of imperialist capitalist relations in the dominated world in the 20th century— was assaulted, and as a result was naturally driven into a struggle against the status quo.

Petite-bourgeois socialism in the metropoles in the 19th century was the first manifestation of this struggle. This socialism was deeply inspired by early Christianity known as “Christian Socialism”.

Later, with the ascendency of Marxism in social movements in the 20th century, petite-bourgeois socialism, emerged and matured in the metropoles in the form of “Non-Revolutionary Marxism” which in general can be called “Academic Marxism”: an eclectic Marxism which emerged from the Frankfurt School in the early 20th century and its variant byproducts are surfacing as phenomena such as Slavoj Žižek, David Harvey, Vivek Chibber and alike in our days.

In the peripheral countries, however, between the 1960s and the 1970s, we again encounter a kind of petite-bourgeois socialism inspired by Christianity. This Christian socialism first emerged in Latin America as “Liberation Theology” and later spread to other parts of the world.

In contrast to 19th century Christian socialism which directly promoted a form of “socialism” inspired by Christianity, 20th century Christianity-inspired socialism now resorted to Marxism and Marxist concepts during the rise of 20th century Marxism. That is, it now interpreted the concepts and values of early Christianity in a Marxist sense, taking advantage of those themes and modifying and rewriting them in its own way.

In Iran, too, the same tendency became a model for the struggle against social oppression by the petite-bourgeoisie in the 1970s. The difference, however, was that in Iran, instead of combining Marxism with the foundations of Christianity, we witnessed the combining of Marxism with the principles of Islam. But this interest in Marxism, since it was merely instrumental, fundamentally artificial and essentially eclectic, could not therefore be a genuine and persistent tendency.(1)

Why?

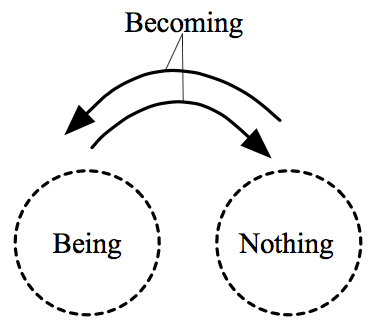

In Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Marx raises a key issue in rejecting Hegel’s conception of the dialectical resolution of contradictions (specifically in the sphere of society), which was later addressed and reflected, in my opinion, in the communist movement in the 1920s and the 1930s as “Antagonistic Contradiction” and “Non-Antagonistic Contradiction”.

Hegel believed in the resolution of a contradiction, in general and categorically, through mediation and by a kind of integration between the two sides of the conflict. One of the fundamental differences between Marx’s dialectics and that of Hegel is also evident in this area.

Marx rejected this. He argued that only those extremes could be resolved through mediation— or through reconciliation if you will— in which the opposite poles were in essence alike: just like the biological opposition between a man and a woman, a distinction in which the parties do not really negate themselves when colliding with each other, but rather necessarily affirm one another and are, in fact, complementary to each other. Here, the result of the biological intersection of the two is neither the negation of the woman nor the negation of the man but rather the affirmation of both — something that manifests itself as the procreation and the preservation of the human species. (In addition to the example above, Marx also mentions the North and South Poles.)

Marx argues that this, however, is not true of those opposite poles in which the poles are in essence opposed to each other— just as the relation between labor and capital reveals; a relationship in which the poles do not affirm each other but rather reject each other and cannot be reconciled. The internal antagonism between the two leads to wealth in one and poverty in the other. The prosperity of capital brings forth misery and deprivation for the worker while gain and prosperity for the worker is a loss to capital. As a result, class reconciliation between the two, in practice, is impossible.(2) In other words, although the two enter into a relationship and find so-called “unity”, the basic point is that the unity between the two is ‘relative, conditional and temporary’ while the antagonism between them is ‘absolute’. And, in fact, antagonistic relations are not resolved by intermingling but by war to the point of annihilation.

Given this principle, and insofar as it relates to our initial discussion, it must be emphasized that the attempt to merge or reconcile inherently hostile and mutually exclusive poles is a futile endeavor and the result cannot be genuine. This fusion is an ephemeral and contradictory amalgam of a unity that will be forcibly disintegrated.

There is a proverb that says, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions”. Here, too, it must be said that the efforts of the militant founding leaders of the OIPM in implementing such an amalgam— undoubtedly done with philanthropic and noble intentions— could only lead to conflict and divergence, that is, to the explosion and disintegration of that unity: the Islamic tendency adhered to Islam and the Marxist tendency rejected Islam. The former did not submit to the latter and the latter in order to solve the problem decided to physically remove the former from the equation. In short, each considered the other an obstacle and the reason for its own failure.

The experience of forcing a bond between two actual extremes; two irreconcilables in this organization— which logically could not have led to anything other than an unavoidable divorce— showed that Islam and Marxism were not compatible and, therefore, cannot be combined. We also witnessed that neither the Islam of this organization was able to maintain its revolutionary tendency without Marxism, nor was the “Marxism” that emerged from this synthetic union able to be a dynamic and revolutionary Marxism.

It is a fact that the objective conditions always place certain necessities before us and demand action from us. But a practical approach to problems can be truly creative and dynamic only if it is in line with revolutionary principles. The attitude of the quasi-Marxist faction of the Mojahedin towards its religious faction was nothing but a kind of pragmatism and was not in line with revolutionary principles and traditions. As a result, it led to what we know. Basically, a pragmatic approach to problems hinders us from solving problems, because often, it simply crosses out and removes problems but does not necessarily resolve them.

The Islamic tendency in this organization, after the removal of “Marxism” from its foundation— i.e., when it returned to its origin and emerged with its true Islamic face— consequently lost its “progressive” and “radical” tendency and in the process of its transmutation eventually metamorphosed into the Mojahedin we know today.

The so-called “Marxist” tendency in this organization also came to naught when it finally gave up on Islam and supposedly decided to return to “Marxist roots”— of which the Peykar Organization was the main emblem— it led to the formalistic and sterile Marxism that the Tudeh Party embodied and represented.(3)

Let’s return to the main point!

The irony was that if in this precarious relationship; in this integration, the real principles of Islam were modified and thus able – albeit formally – to be “radicalized” and to take a step forward; in other words, if this Islam, as a “progressive” and a “vanguard” Islam had managed to become a source of inspiration for the nationalist-religious intellectuals within society, the other side of this integration, i.e., the so-called “Marxism” of the OIPM, had to have retreated from true Marxism and in a sense digressed, unlike the Islamic faction, in order to be modified. That is, it had to be a kind of Marxism that could be combined with Islam. And this, in fact, was the requisite of the merge: without reactionary Islam being promoted to “progressive Islam” and Marxism being reduced to an “eclectic Marxism”, this combination; this dualism would never have been possible.

This requisite, however, was fundamentally flawed because the basic principles of both doctrines had to be modified and manipulated so that the two could be gathered together in one body. Yet, neither Islam can really be democratized, nor is Marxism reducible— eclectic Marxism is not Marxism; it is a toy. And perhaps, the faction that broke off from Islam and turned to Marxism was aware of this fact, although unfortunately the Marxism that it turned to was formalistic and inorganic instead of creative and in accordance to the conditions of Iranian society.

Conclusion:

The philosophical dualism of the OIPM was, in fact, a futile attempt to reconcile the irreconcilable. And since such an attempt is fundamentally illusory and unsustainable, what at first seems to be the reconciliation between the irreconcilable, in its logical continuation, inevitably leads to conflict.(4) What seems to be a marriage between the unmarriageable necessarily leads to divorce. What seems to be synthesis or transcendence leads to regression; to the starting point, that is, to the very fundamental contradiction: Religion versus Marxism, and Marxism versus Religion.

In conclusion, the end result of mixing the immiscible can only move in one direction, and that direction is certainly not unity but rather the expiration of unity. Marxism and religion are not parallel but opposite, and are not intertwined, but in esoteric conflict and antagonism.

A. Behrang

April 2022

Notes:

1. Of course, this does not mean that we should ignore or downplay the valuable effects and combative achievements resulting from this approach to Marxism. On the contrary, the radicalism and the fight to the death of that generation of the Mojahedin created a shining page in the history of our people’s struggles; a page that is both praiseworthy and unforgettable.

2. “Actual extremes cannot be mediated with each other precisely because they are actual extremes. But neither are they in need of mediation, because they are opposed in essence. They have nothing in common with one another; they neither need nor complement one another. The one does not carry in its womb the yearning, the need, the anticipation of the other.” Critique of Hegel’s philosophy of law, Karl Marx.

3. As a result, The Peykar Organization became so subjective and dogmatic that from a historical point of view, overnight, it lost the truly militant forces that had been attracted to it. By having a subjective understanding of the hard facts of class struggle in Iran, this organization was slapped so badly by those very facts that when the organization came to its senses, it was practically broken under the blow of the dictatorship. The Peykar Organization very clearly collapsed under the unbearable burden of the banner of ‘Open and Overt Political Work’ which it had wrongly assumed under the conditions of a naked dictatorship. An inevitable fact that could be denied or ignored only in words— although, the remnants of the Peykar Organization at the time continued to insist that ‘the cause of the blows and the disintegration of this organization was not the wave of repression but rather their internal theoretical differences and disagreements’!!

The fact remains that the Peykar Organization was never able to revive itself. And indeed, how could an organization that had suffered fatal blows as a result of its fiery policy of ‘Open Political Activity’ under a naked dictatorship retake the same flag and revive itself?! Of course, we also should not forget the undeniable fact that basically the political organizations of the day gained their momentum not in the course of peaceful political work under dictatorial conditions but as a result of the exceptional circumstances arisen from the uprising in 1979. Because gaining such a force under the conditions of a naked and widespread dictatorship through mere political activity neither existed nor is it likely to ever exist.

4. What we mean by conflict here is, in fact, separation. However, due to the pragmatic approach of the quasi-Marxist faction of this organization, it actually crystallized into a bloody war.

2 Comments

Rachel

Thank you for this article which explained as to how and why the Mojahedin’s attempt to mix religion and Marxism, though doable, was unsustainable. Beyond that, this article nowadays is more relevant than ever. Yes indeed, whether we talk about Christian or Islamic liberation theology, it is based on idealism rather than dialectical materialism. When the elementary understanding that the cause of oppression ultimately comes from the basic contradiction between labour and capital is lacking, then all best efforts will eventually fail. For example, in the 60s and 70s, feminists, Latin Americans, and black theologians struggled to unite into a cohesive body. Rather than focusing on capitalism as the source of oppression, In 1975, when they all came to the Theology of the Americas conference in Detroit, there were fierce clashes. The black theologians blamed the white oppressors for racism while the feminists branded a male dominated society to be the culprit. Each group insisted on prioritizing its own concerns whether it be race or gender. Thus, the history of liberation theology is a very splintered one. Presently, the recent historic redistribution of wealth in the U.S. has prompted a resurgence of Christian leftism. Groups like the Poor People’s Campaign and the Red Letter Christians have taken to the streets. When Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won her Congressional seat as a Socialist Democrat, she published an article in the Catholic American magazine linking her leftist politics to her Christian faith. Recently, a liberation theology professor was invited to Richard Wolfe’s podcast ‘Economic Update’ to discuss the importance of ‘Christian Marxism’ in freeing the oppressed. Indeed, the Christian left (the union between socialism and religion) has been energized making liberation theology a movement considered dead 20 years ago, popular once again and ultimately doomed to fall apart.

A. Behrang

Thank you for your comment. With your line of argument and the example of the 1975 Detriot Confrence, you have actually covered an aspect that I didn’t deal with in my post: Liberation Theology in the West and its resurgence today.